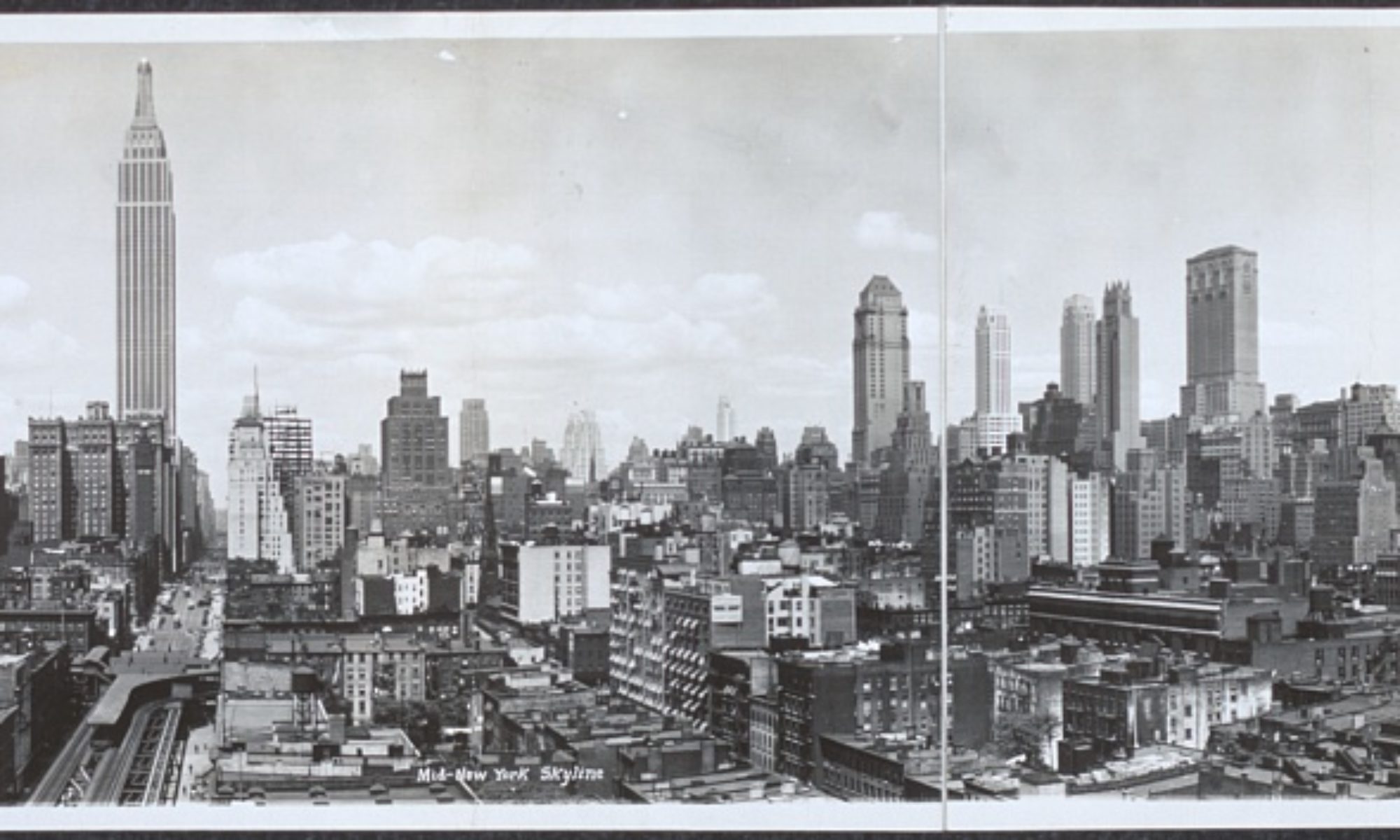

The forthcoming Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis features an excellent article from the historian Elisabeth Koning, an alum of the MA program in American Studies, which draws on the work begun in her thesis. Koning excavated Dutch translations and adaptations of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and developed a profound yet nuanced argument about the diffusion of American popular culture. She has extended and refined that research here.

Zwarte Piet, een blackfacepersonage: een eeuw aan blackfacevermaak in Nederland [Black Pete, a blackface character: a century of blackface amusement in the Netherlands]

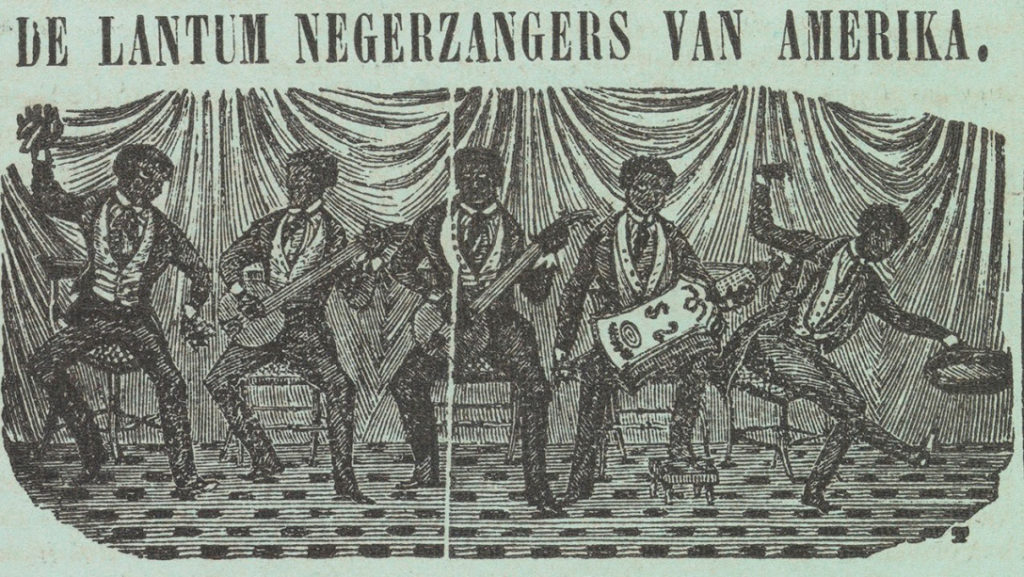

Abstract: In 1847 the Ethiopian Serenaders successfully introduced American blackface minstrelsy to a Dutch public. A few years later the publication of the Dutch translation of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1853) and the subsequent ‘Tom-play’ led white Dutch actors to perform in blackface. Blackface performances functioned not merely as entertainment, but perpetuated a stereotypical white image of black people. During that same period the Amsterdam-based teacher Jan Schenkman published a children’s book including a black servant (St. Nikolaas en zijn knecht, 1850). The servant was known as Black Pete and became established in the Saint Nicolas tradition. In the years to come, Black Pete, generally a white person wearing a blackface mask, leaned heavily on the same elements that made the blackface minstrel dandy type a success: edified clothing, a blackface mask, and antiemancipation humour.

Zwarte Piet en de blackfacetraditie [in Dutch]