In 1917, Max Weber said, about the United States, that “it is often possible to see things in their purest form there.” He was talking then about scholarship as a vocation (“Wissenschaft als Beruf“), reflecting on the “Americanization” of German academic life, but it was a broader theme running through his work.

“America Inside Out” is an MA seminar in our program about international perspectives of the United States. Among its texts is Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904-1905). That book grew out of a trip to the U.S. in 1904, where, as the American Studies program’s George Blaustein writes in the New Republic, Weber “faced the lurid enormity of capitalism.” Looking upon Chicago (the focus of the BA course Metropolitan America), with its slaughterhouses, the strikes, the multi-ethnic working classes, Weber felt he was looking at “a man whose skin has been peeled off and whose intestines are seen at work.”

“America Inside Out” is an MA seminar in our program about international perspectives of the United States. Among its texts is Weber’s The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904-1905). That book grew out of a trip to the U.S. in 1904, where, as the American Studies program’s George Blaustein writes in the New Republic, Weber “faced the lurid enormity of capitalism.” Looking upon Chicago (the focus of the BA course Metropolitan America), with its slaughterhouses, the strikes, the multi-ethnic working classes, Weber felt he was looking at “a man whose skin has been peeled off and whose intestines are seen at work.”

Weber theorized the rise of capitalism, the state and its relationship to violence, the role of “charisma” in politics. Again and again he returned, as we still do, to the vocation—the calling—as both a crushing predicament and a noble aspiration. He died 100 years ago, in a later wave of the Spanish flu. It is poignant to read him now, in our own era of pandemic and cataclysm. It might offer consolation. Or it might fail to console.

Read those reflections on the relevance and irrelevance of Weber’s writings in an era of pandemic and political upheaval here: “Searching for Consolation in Max Weber’s Work Ethic,” The New Republic (July 2, 2020). Read them in Dutch translation here: “De onttovenaar van de wereld,” De Groene Amsterdammer 144:25 (June 17, 2020), p. 36-41.

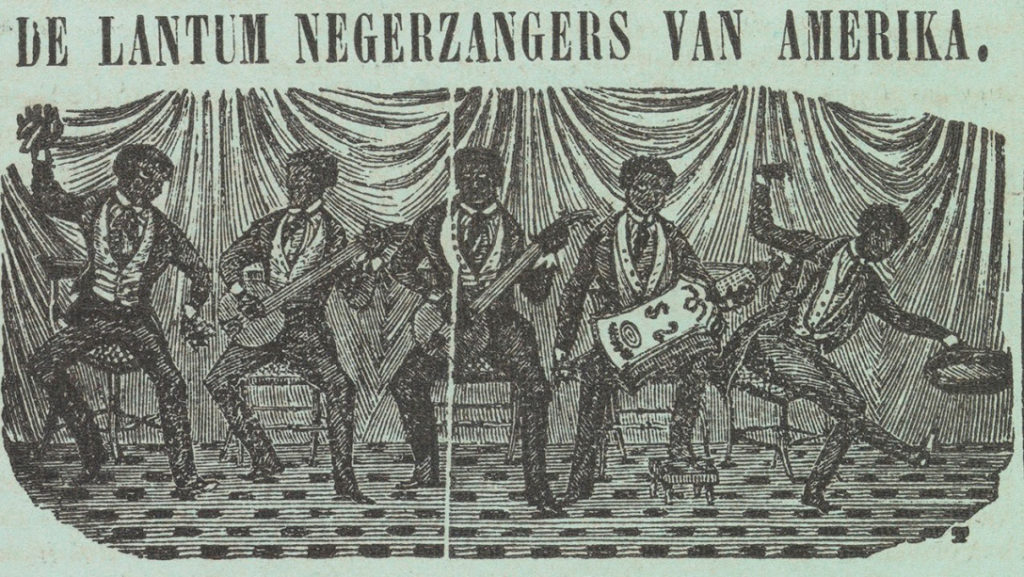

One of my favorite texts to discuss in a seminar is James Baldwin’s “Stranger in the Village,” published in Harper’s in 1953. “From all available evidence no black man had ever set foot in this tiny Swiss village before I came,” Baldwin begins. This is where the MA Seminar “America Inside Out: International Perspectives on the United States” starts: Baldwin’s magisterial essay about America, Europe, and the West, because it both typifies and challenges much that we talk about when we talk about the “American Century.” Its last paragraph rewards quotation:

One of my favorite texts to discuss in a seminar is James Baldwin’s “Stranger in the Village,” published in Harper’s in 1953. “From all available evidence no black man had ever set foot in this tiny Swiss village before I came,” Baldwin begins. This is where the MA Seminar “America Inside Out: International Perspectives on the United States” starts: Baldwin’s magisterial essay about America, Europe, and the West, because it both typifies and challenges much that we talk about when we talk about the “American Century.” Its last paragraph rewards quotation: